Hydroplane Programme Covers

Words: James Pernikoff

Pictures: Stephen Lane, Jack Lowe, Kent O. Smith, Jr.

Unlimited hydroplanes (which I will refer to simply as "hydros") are the world's fastest closed-course racing boats. In fact only top fuel drag boats and world speed record boats are faster, and they do all their business in a straight line.

The hydros run an annual circuit of 9–12 races every summer in the U.S. and Canada, on river and protected lake courses, both fresh and salt water. The courses are 2 or 2-½ mile ovals or triangles marked by buoys and run counter-clockwise (or anti-clockwise, if you prefer). Many of the venues have been hosting races continually for years: Detroit since 1904, Seattle since 1950, and Madison, Indiana (on the Ohio River) since 1966 are the longest-running sites. Detroit was the birthplace of the sport but Seattle is where most of the teams are based now.

Although National Championships for both boats and drivers are awarded annually, and winning these is the top honor in the sport, that wasn't always the case. For many years, winning the most important race of the year, the APBA Gold Cup, was considered more significant than the year-long series. The Gold Cup was first competed for in 1904, and even today winning it is on a par with winning the Indy 500, Le Mans 24 Hours, or Grand Prix of Monaco.

For over 50 years, the Gold Cup was really a race between yacht clubs, not between boats or boat teams. It was run along the same lines as international trophies like the America's Cup or the Schneider Trophy: each boat represented a yacht club, and the club of the winning boat got to display the trophy and to determine the site of the following year's race.

In the teens, a Detroit industrialist named Gar Wood became the first superstar of powerboat racing. To ensure that Detroit got to keep the Gold Cup, he built an ever-more powerful series of boats, each called Miss Detroit. He became so dominant that the APBA forced him out by banning the Unlimited-class (U) boats and creating a new class of smaller Gold Cup (G) boats.

Wood wasn't about to give up his power, especially with the V12 Liberty aircraft engine now becoming available. So he turned his attention to the international Harmsworth Trophy, which was similar in concept to the Gold Cup, except being between countries. Wood renamed his boats Miss America and kept on going. When one engine wasn't enough, he built boats for two; when that wasn't enough, he built a boat for four! Naturally keeping an eye on four V12s was too much for one man; all Unlimited boats of that period had a crew of 2: driver and throttleman, similar to today's offshore boats.

As with other international speed contests, the usual protagonists for the Harmsworth were the U.S. and Britain. Thanks mainly to Gar Wood, the trophy spent most of its time in the States in the 20s and 30s, but occasionally one of the Miss England boats would win and get the trophy, but always temporarily, it seems.

Eventually the APBA relented and opened the Gold Cup to U-class boats again, but the G-class remained, and often their nimbleness made up for their power disadvantage. In fact through the 30s the Depression made Unlimited-class boats almost unaffordable, and the Gold Cup class, with cheaper single-engine craft, predominated. However, the Unlimited-class boats, which were now powered by purpose-built Packard marine engines, would form the basis for the famous PT boats of World War II.

These were all "step" hydroplanes, which had a crosswise step on the bottom of the hull, similar to those seen on flying boats and seaplane floats. At speed, the boat would ride the step, reducing friction with the water. Later on some boats had multiple steps and experimented with different propellor locations. A change did come, though, from a very unusual source.

In the mid-30s, China, engaged in an increasingly bitter war with Japan, ordered a dozen small, fast suicide boats from the U.S. government. They, naturally, turned to a major raceboat builder, the Ventnor Boat Works of New Jersey. But when Ventnor's designer, Adolph Apel, put a simulated version of the explosive charge in the nose of the boat, it was so nose-heavy that it would not gain enough speed to ride up on the step.

It happened that Ventnor also made water skis, so Apel tried taking the biggest pair of skis he could find and affixing them to the sides of his boat's nose. After some fiddling, he found the right position and angle to allow the front of the boat to ride up on the skis and gain speed. He then removed the skis and replaced them with a pair of fairings, called sponsons. In this form, 11 of the 12 boats were delivered to China, where their eventual fate is unknown.

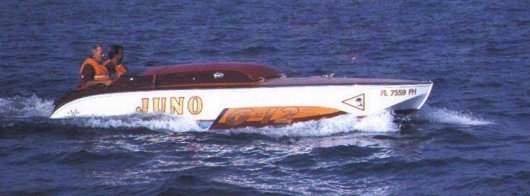

For some reason, the last boat was never picked up. It was decided to race the boat, and, named Juno, it proved conclusively faster than any of the opposition. Eventually Ventnor became famous building numerous copies of what were now called "three-point hydroplanes." One of the best known, My Sin, was later bought by bandleader Guy Lombardo, who renamed it Tempo VI and won a postwar Gold Cup with it.

So what is this "three-point suspension?" Now the step has been eliminated, and the boat at speed is riding on only three points: the very aft edge of each sponson, and the very back end of the hull. This reduced drag even further, and the increased width made the boats more stable in the turns. The increase in speed over fast step-hulls was still not all that great, and step hydros would continue to win races, also, until the next, and biggest, innovation came along, in 1950.

The first big change in Unlimiteds after World War II was the fairly rapid availability of the Allison V12 aircraft engine. While some early attempts to shoehorn Allisons into boats originally designed for smaller engines were less than successful, the Allison ultimately became the engine to have. Since the bigger Unlimited-class boats could now make do with only one engine, the smaller Gold Cup class died out fairly quickly.

While the Allison was the first big change after the war, a much bigger change was coming, and it came from Seattle.

A Boeing engineer (and part-time boat racer) named Ted Jones had what he felt was a revolutionary idea but not the money to carry it out. He eventually linked up with a Seattle auto dealer (and part-time racing-boat owner) named Stanley Sayres, who was having his small 225-cubic inch hydro, Slo-Mo-Shun II, rebuilt at the shop of experienced boatbuilder Anchor Jensen. Jones persuaded Sayres to fund the building of a new 225-class hydro to test his theory.

The new boat, Slo-Mo-Shun III, was so promising that Sayres immediately shelved it and had Jones and Jensen build him a full-fledged unlimited named Slo-Mo-Shun IV. This is the boat that would stand the racing world on its ear and usher in the "modern era" of hydroplane racing. (Ironically enough, in 1950, the same year as the start of the "modern era" in Grand Prix motor racing!)

Sayres first went after one of his targets, the world water speed record, which had been held since before the war by Malcolm Campbell at over 141 MPH. Sayres and Jones showed the potential of the new hull by going out on Seattle's Lake Washington in the summer of 1950 and shattering Campbell's record by nearly 20 MPH!

Naturally, this raised much concern in Detroit when Slo-Mo IV showed up for the 1950 Gold Cup race, another of Sayre's targets. Pundits said that while the boat was obviously fast in the straights, it wouldn't turn worth a darn. Ted Jones proved them wrong by winning the race as he pleased, even lapping the entire field in one of the preliminary heats. Now all the other designers headed straight for their drawing boards, since the new boat had instantly obsoleted the entire Unlimited field. It also meant that the 1951 Gold Cup race would be held in Seattle, the first time the race had ever been held west of Minnesota.

What made Slo-Mo IV so fast? It was the first successful "proprider." By paying more attention to the topside aerodynamics—for the first time the sponsons looked like an integral part of the boat and not as add-ons—Jones and Jensen got the back end of the boat to ride on only half the propeller. The hull itself was clear of the water at speed, substantially cutting the water drag. When "on plane," the only parts of a three-point proprider that are in the water are the extreme back ends of the two sponsons, half the propeller (those make up the "three points"), the rudder, and a large fixed blade on the left side of the boat, called a skid fin, which enables the boat to turn left. The fact that only half the prop is submerged is what causes the big "roostertail" of water behind the boat.

Within a few years the step hydros and Ventnor-type three-pointers would disappear in favor of more propriders. The only thing that prolonged their lives is the fact that Sayres was only interested in the Gold Cup and did not run the full circuit. The new boats were obviously copies of the Slo-Mo, but the best copy came from the same team: Slo-Mo-Shun V joined the effort for 1951, and was an even better raceboat, since it was optimized for closed-course racing, whereas the IV had been primarily aimed at the straightaway record (which, by the way, it raised to an amazing 178 MPH; it was, however, the last prop-driven boat to hold the absolute water speed record, as jet-propelled craft soon boosted the record substantially).

The Gold Cup stayed in Seattle awhile, since between them Slo-Mo IV and V won the race five years in a row. By the time the Slo-Mo-Shun era ended with Stan Sayre's death, other Seattle teams had been formed to keep the rivalry with Detroit in full cry.

As the 50s progressed, several changes became apparent. First, the Rolls-Royce Merlin supplanted the Allison as the engine of choice, due to superior supercharging, though Allisons would continue to be widely used. Second, as costs rose, the first commercial sponsors began to appear, on boats like Miss Bardahl, Miss Thriftway, and Miss Pay-N-Save. Also, community-owned boats became popular, such as Miss Burien, Miss Spokane, and the most famous, Miss Madison (of Indiana), which is still active.

The old Harmsworth Trophy races revived after a twenty-year hiatus, except now the opposition came from Canada, in the form of a series of boats called Miss Supertest. Due to the rules, the Canadian boats could use the Rolls Merlin (and later, the larger Griffon), while the U.S. boats had to make do with Allisons. This, in part, allowed the Canadians to win the Trophy in 1959 through 1961, at which point the challenge became dormant again. In recent years there have been new Harmsworth races, but for offshore or tunnel-hull boats, not Unlimiteds.

The next big change came after 1960, a year in which the Gold Cup was declared "no contest" due to rough water on Nevada's Lake Tahoe (Reno's Bill Stead had won the 1959 race). Henceforth the race was to between boat teams and not yacht clubs, and the race each year would go to the highest bidder. Although this opened up holding the race to other venues, eventually Detroit began to outbid all others in the late 80s, and the race's home ever since has been its original home. (Detroit has even asked the APBA to declare it the permanent home of the Gold Cup race, but so far that has not been done.)

By now, even though the Gold Cup would continue to remain the most important race, the National Championship had by now become more important. After a period of relative parity, the early 60s became a time of domination. First, in 1960 through 1962, Miss Thriftway, driven by the great Bill Muncey, won 3 straight championships. Then, after that team called it quits, Miss Bardahl, driven by the also-great Ron Musson, followed up with 3 more in 1963 through 1965.

In 1962 a driver named Roy Duby raised the straightaway speed record for prop-driven boats (now a separate category) to just over 200 MPH. That record would not be broken until 2000!

Although the boats had gotten faster since the days of Slo-Mo IV, their basic shape had remained about the same. The sport had had a remarkably safe record, with only one driver fatality since 1951. Sadly, that would all soon change in a big way.

19 June 1966 was the blackest day in Unlimited history, as three top drivers (including Ron Musson) died in two separate accidents during the second day of the President's Cup regatta on the Potomac River in Washington. The hydro community wondered how their 15-year fatality list had doubled in one afternoon. If that wasn't enough, another top driver was killed 2 weeks later in the Gold Cup race, and 2 more top men died in 1967 and 1968.

What had happened? Truthfully, the sport had been lucky, as a number of drivers had survived some pretty bad crashes through the years. The boats were going ever faster, while still using what was basically 1950 technology. They were running on the ragged edge, and it was all too easy to go over that edge.

One thing many of the accidents had in common was that when the boat began to lose control, the round nose, which looked like a shovel from above, would dig into the water and act just like one, causing the boat to rapidly decelerate. With the predominantly wooden construction, this usually led to total disintegration, with the body of the driver (hopefully still alive) left floating amongst kindling wood.

As a result, designers began looking into cutting the nose back to behind the tips of the two sponsons. This led to what became known as the "picklefork bow" as the protruding tips of the sponsons resembled tines of a fork. The section between the sponsons now had a straight leading edge and looked more like the airfoil section it really was, which led to the center section often being called a "ram wing."

Although several conservative picklefork boats appeared by 1968, the first definitive one was 1970's Pride Of Pay N' Pak, designed by Ron Jones, the son of Ted Jones. The new boat featured some other pet ideas of Jones, including the use of twin supercharged Chrysler hemi automotive engines, and the fact that the boat was what had become known (incorrectly) as a "cabover," in which the driver sits ahead of the engine(s). In this form the boat was unsuccessful, so for 1971 it was converted to a conventional, front-engined, Merlin-powered boat, and in this form it became a consistent winner. Most of the new hulls built during the 70s, whether built by Jones or not, had a similar hull design, and the sport's safety record improved.

Another change which came along in the early 70s was the development of a practical turbocharging setup for the Allison V12, which helped close the gap to the Merlins. While the Rolls engine remained preferable, Allisons continued to race well, and one is still at it in the year 2000.

Ron Jones' next design for Pay N' Pak was even more revolutionary. Although the 1973 boat's most distinctive feature was a small, high-mounted rear wing, the real change was under the skin, as this was the first hydro to be built using aircraft-style aluminum honeycomb. This made the boat stronger and lighter, and minimized the threat of disintegration or sinking. The boat proved its mettle by winning three straight championships with 2 different drivers.

When the Pay N' Pak team pulled out after 1975, with no more worlds to conquer, owner Dave Heerensperger put everything up for sale. It was bought, lock, stock, and barrel, by Bill Muncey who, after a three-year winless streak, decided the time had come for him to become an owner-driver. Muncey proved the 1973 hull was still competitive by driving it, under Atlas Van Lines sponsorship, to an unprecedented fourth-straight national championship.

Muncey then turned his attention to a sleek cabover hull, designed by crew chief Jim Lucero, that had been part of his purchase. This boat was lower and wider than anything than had gone before, with an enormous rear wing to provide aft-end lift. Muncey had always been suspicious of cabovers, but took quickly to this one. After working out the bugs, the boat, nicknamed the "Blue Blaster," became almost unbeatable and replaced its predecessor as the winningest hydro of all time. It was the first cabover to win the title, and in fact no boat with the driver sitting behind the engine would ever win another. The rear wing design was so good that every Unlimited today uses essentially the same design. Muncey worked his career win total to an astounding 62.

Miss Budweiser owner Bernie Little had entered his first Unlimited race in 1964 and had already tasted success, starting with a boat that had won 3 straight titles in 1969 to 1971. To beat Muncey, Little ordered a new winged cabover from Ron Jones to use the bigger Rolls-Royce Griffon engine, which he had cornered the market on. The first such boat, in 1979, was unsuccessful, and was destroyed in a post-season attempt at the world straightaway speed record. Its replacement in 1980 was far better, and soon it was Muncey playing catch-up.

Unfortunately, this led to more tragedy. At the 1981 season-ending race in Acapulco, Muncey took a chance with a setup which would be fast but flighty; in fact all his friends told him not to do it. Fittingly, Muncey was out in front when the boat blew over backwards, dumping him out (drivers still did not use belts then) and landing on him. Sadly, a similar fate was to befall Miss Budweiser driver Dean Chenoweth (who had inherited the mantle of winningest active driver) when his boat blew over during a practice session on the Columbia River the following summer.

Suddenly, it was 1966 all over again, as the sport's 2 all-time winningest drivers had been killed within 9 months of each other. Now, due to the new construction materials, the boats were surviving (Chenoweth's was race-ready just over a week after his crash!), so it was realized the trick now was to keep the drivers safely inside.

This was done in two steps. In 1983, the new Atlas Van Lines was redesigned to put driver Chip Hanauer lower in the boat, in a reinforced cockpit with a full racing harness, a roll bar, an oxygen supply hooked to his helmet, and an escape hatch in the bottom of the boat. This was an improvement, but the driver was still out in the open.

Finally, in 1986, after experimenting with other designs, the new Miss Budweiser added the last touch: a cockpit canopy cut down from that of an F-16 fighter jet. Fitted with radios and rear-view mirrors, the driver was now in a safe cocoon. This design became mandatory for all Unlimiteds for 1989, and eventually became used on drag boats and tunnel-hulls, as well as certain limited-class hydros and offshore powerboats. As a result, no Unlimited driver has lost his life in a boat since Chenoweth in 1982.

While all this was happening, a new power source was whooshing its way into prominence.

After the Muncey/Chenoweth tragedies, hydro designers sought to minimize the threat of blowover accidents. The thought was to give the driver more control over the attitude of the boat, especially at the front end. The result was the trimming back of the front of the central ram wing, and replacing it with a separate airfoil surface with a movable trailing edge, called a canard.

Initially the canards could only be adjusted in the pits, but soon designers gave the drivers a foot pedal, with which they could adjust the angle of the canard in flight, much as drivers of Chaparral sports racing cars were able to do in the mid-60s. In addition some boats featured a large gap between the canard and the front of the ram wing. It was hoped that if the front of the boat began to rise, enough air would flow through this "slot" to keep the boat from blowing over.

In actual practice, these features helped somewhat, but there were still times when things happened so quickly that the driver could do nothing about it. Blowovers still happen far too frequently, but thanks to the modern construction materials and the enclosed safety cockpit, both boats and drivers usually survive crashes which would have been fatal just a generation before. Often a driver involved in a devastating wreck will be back in another boat before the end of the day. In one instance, a boat which flipped on its back in a preliminary heat was repaired and came back to win the final heat later in the same day!

Today the canards have tended to have been moved forward of the center fuselage, so they run continuously from sponson to sponson. In some cases the entire front airfoil is movable, but those boats usually still have some sort of fixed strut to provide some rigidity to the fronts of the sponsons. In addition, several designers have tried different configurations of ram wing, including so-called two-wing and three-wing designs, but those have generally been disappointing. Attempts to design radically-different boats, such as four-point hydros, have all been dismal failures.

While all these safety improvements were happening, another, more fundamental change occurred. In 1980, Pay N' Pak owner Dave Heerensperger returned with another innovation. He entered a boat powered by a Lycoming T55 turbine engine. While turbines had been tried before (notably a much-ballyhooed twin-turbine boat in the mid-70s), all had been failures. This time there was much more promise. While the boat only won once in 2 years of competition, it was realized that this was the future.

By 1984, turbine boats were beginning to appear in numbers, and one of these, a new Atlas Van Lines, solved the riddle of making turbine boats fast. Since turbine engines spool up slowly, the trick was to keep the engine running at speed as much as possible. Clearly this meant increasing cornering speeds, and by tweaking the design parameters (the boat didn't actually look all that different), Jim Lucero got the new boat to corner faster than any previous Unlimited. Today's boats don't actually run that much faster in a straight line than those of the 60s and 70s (which may explain why it took 38 years to break the straightaway record!), but cornering speeds, and hence lap speeds, are much greater, much as has happened in land-based motor sports.

This new Atlas, owned by Bill Muncey's widow Fran and driven by his hand-picked successor, Chip Hanauer, became Miller American in 1985, and became the first turbine Unlimited to win the national championship. While V12-powered boats were able to win some races in the next few years (mainly on salt water, where the turbines still had problems with salt ingestion), by decade's end the turbines had conquered all, and no piston boat ever won another championship.

At least one attempt was made to try a different turbine engine, but ultimately everyone settled on the same T55-L-7. This engine, which had been used on the CH-47A model of Boeing's Chinook heavy-lift helicopter, became available when the U.S. Army decided to put a more powerful version of this engine in all its Chinooks. (Several hydro teams tried the more-powerful L-11 version before it was banned.) Compared to the aircraft V12s, the T55 develops similar power and is smaller, lighter, simpler, more reliable, and easier to find parts for. After a series of "hot end" failures, the UHRA put a limit on engine speed, with stiff penalties for violation, which ended that problem. More recently, they have added a fuel-flow valve (akin to CART's pop-off valve, perhaps?) in an attempt to level the playing field. "Unlimited" racing is a lot less unlimited than it used to be (again, like its land-based counterparts)!

When Miss Budweiser finally left its Griffons behind and went turbine in 1986 (with the same boat that introduced the definitive canopy design), everyone knew the piston engine, and its thunder, was history. The last of the classic Muncey-Budweiser duels was in 1990, when Chip Hanauer won a hotly-contested title in Miss Circus Circus. At that point, Fran Muncey and Chip both announced their retirements. The equipment was sold to Winston Eagle owner Steve Woomer, who had some good years ahead, but never quite put it all together to win the championship. Muncey's crew chief, Dave Villwock, later turned to driving, very successfully.

The 90s were effectively a Miss Budweiser decade, especially when Bernie Little lured Chip Hanauer out of retirement. The combination of the best team and best driver led to quite a few more wins until Chip quit again. The only real competition to Bud during this period came from former also-ran Fred Leland, who upgraded his program substantially and, with Villwock driving, won 2 titles with a boat called PICO American Dream. After Hanauer retired, Little persuaded Villwock to switch to Budweiser (for whom he still drives). Ironically, Leland got Hanauer to unretire a second time, and he won 3 races in PICO in 1999 before retiring for good! One reason Chip said that this was final was the fact that those three wins brought his career total up to 61, just one behind his mentor, Bill Muncey, and Hanauer felt he owed Bill the honor of remaining the all-time leading winner. Of course, Dave Villwock is now the active winningest driver, and if he stays with Miss Budweiser, who knows how far is up?

So that's where we are. Each race today has from 8 to 12 turbine-powered, high-winged, enclosed-canopied, pickleforked cabovers with front canards, built from aluminum honeycomb, carbon fiber, fiberglass, and, yes, still some wood. Miss Budweiser is the boat to beat, but there is much good competition behind, and a sole Allison-powered craft usually brings up the rear, reminding everyone of the days when these could truly be called "thunderboats." Speeds are certainly higher (the current qualifying lap record is about 172 MPH on a 2-½ mile course), but I think I prefer the days of Bill Muncey's Blue Blaster, when the lap record was only 140 MPH, but a fleet of six hydros charging for the start of a race sounded like a squadron of Spitfires scrambling in 1940!

Today, as seemingly in every generation, people are predicting the death of the sport, but it appears that as long as Man has the desire to go faster on any medium, Unlimited Hydroplanes will be part of the scene.